Americans are perhaps the standard bearers of the “barbecue.” Backyards and parks in the United States are full of people gathering around sauce-slathered chicken and other meats.

But famed as America’s grill skills may be, many would claim it can’t hold a glowing charcoal ember to the meat-charring culture of, say, Argentina or South Africa.

History isn’t clear on where the term “barbecue” comes from – one explanation is that it comes from “barbacoa,” a term used by Spanish explorers to describe the Caribbean’s indigenous Taino people’s cooking technique.

In any case, barbecue as we know it today covers multiple cooking methods: On grills, above fire pits, under the ground and in clay ovens.

There are regional variations and customs in destinations from South America to Africa to Asia.

Read on for further proof that the lip-smacking barbecue experience is a universal tradition, not just an American one.

The South African braai (“barbecue” in Afrikaans) is the nation’s top culinary custom.

Here, the frequent gathering of friends and family over grilled, juicy cuts of steak, sausage and chicken sosaties (skewers) cuts through all racial and socioeconomic lines.

And no place does “Sunday Funday” quite like the townships, where shisa nyama (“burn meat” in Zulu) venues elevate the braai experience with on-site butchers, cooks, drinks and party-starting DJs. Chicago native and model Unique Love spent three years living in Cape Town and fondly recalls her first shisa nyama.

“Having a braai in Cape Town’s Mzoli’s Meat felt like home,” she says. “After eating, I never wanted to [leave] because the community’s ambiance felt comforting.”

Though its place as the world’s top consumer of beef fluctuates each year, many would claim Argentina will forever be the grande dame of barbecued meats. Like South Africa’s braai culture, Argentina’s affinity for the grill is more entrenched than in the States.

Attending a sociable, gut-busting asado (“barbecue”) on an almost weekly basis is the norm.

Though a variety of meats and cuts can be experienced at any gathering, Argentinian Guillermo Pernot, chef-partner of Cuba Libre Restaurant & Rum Bar, insists: “For the absolute best asado, one should cook a sweet pork and beef sausage, sweetbreads, thigh intestines and blood sausages.”

Other asado tips from the two-time winner of the James Beard Award include using coarse salt to coat meats and to have the “indispensable” chimichurri – a sauce and marinade that usually consists of parsley, garlic, oregano, vinegar and chili flakes – at the ready.

Yakitori, a favorite in Japan, consists of diced chicken assembled onto bamboo skewers and cooked over a smoldering layer of charcoal.

Yakitori variations are labeled by chicken parts (strips of chicken skin make up “towikawa” and “negima” consists of thigh meat with leeks).

Its definition has expanded to include any grilled, skewered food, including vegetables, seafood, pork and beef. While there are several ways to enjoy authentic yakitori in Japan, travel blogger Tanya Spaulding shares her tips for maximum enjoyment.

“The best way to savor yakitori is either from a street vendor, or sitting on the floor in your yukata (a sort of summer kimono), cooking your skewers over the shichirin (a small charcoal grill) in the middle of your table,” she claims.

Barbecue enthusiasts with sizable appetites will love Brazil’s churrasco (Portuguese and Spanish for “barbecue”).

Most visitors to Brazil will get their barbecue fix at a churrascaria, where restaurant servers provide an endless supply of grilled meat cuts directly to patrons’ tables. While Brazilian churrasco might be the most famous, it’s found in several other countries, including Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala and Portugal.

Dan Clarke, director of RealWorld Holidays, who frequents South America, believes Brazilian barbecues offer more options for vegetarians than neighboring, meat-loving Argentina.

“At an Argentinian asado, you’re really stuck with the salad and fries,” he says. “But it’s much better in Brazil because most churrascarias feature salad bars with dozens of kinds of fresh salads, pasta salads, pickles, breads, olives and all the other sides you could wish for.”

Lechon (Spanish for “suckling pig”) features a whole, impaled pig spit-roasted over a charcoal bed or in an oven. Many Filipinos declare the tasty, porky treat to be their national dish although the same claim is made by Puerto Ricans.

The lechon cooked on the Filipino island of Cebu is often considered the best in the country, if not the world.

Fun fact: Every June 24 in Balayan, Philippines, the locals pay a special, religious-themed homage to roasted pig at the Parada ng Lechon (Parade of Spit-Roast Pig).

It involves lechons getting blessed at a church mass followed by a lively parade of floats, music, water guns (for the baptism) and lechons “dressed” in outlandish garments and accessories.

Tandoor (India)

It’s true: that iconic Indian tandoori chicken you’ve known (and perhaps loved) for ages is considered a barbecue dish.

Tandoori food derives its name from the tandoor, the cauldron-like clay oven in which dishes such as naan bread, chicken, seafood and other meats are cooked under high-heat charcoal.

“The art of the tandoor originated centuries ago as a nomadic style of cooking in Central Asia [where] food was cooked on charcoal pits and meat was spit-roasted,” says Manjit Gill, corporate chef for ITC Hotels and an Indian celebrity cook behind several acclaimed restaurants including Bukhara in New Delhi.

“The Tandoori cuisine as we know it today was introduced in the late 1940s in post-partition India, when people discovered that it was a better medium to cook meat in a tandoor rather than on the spit.”

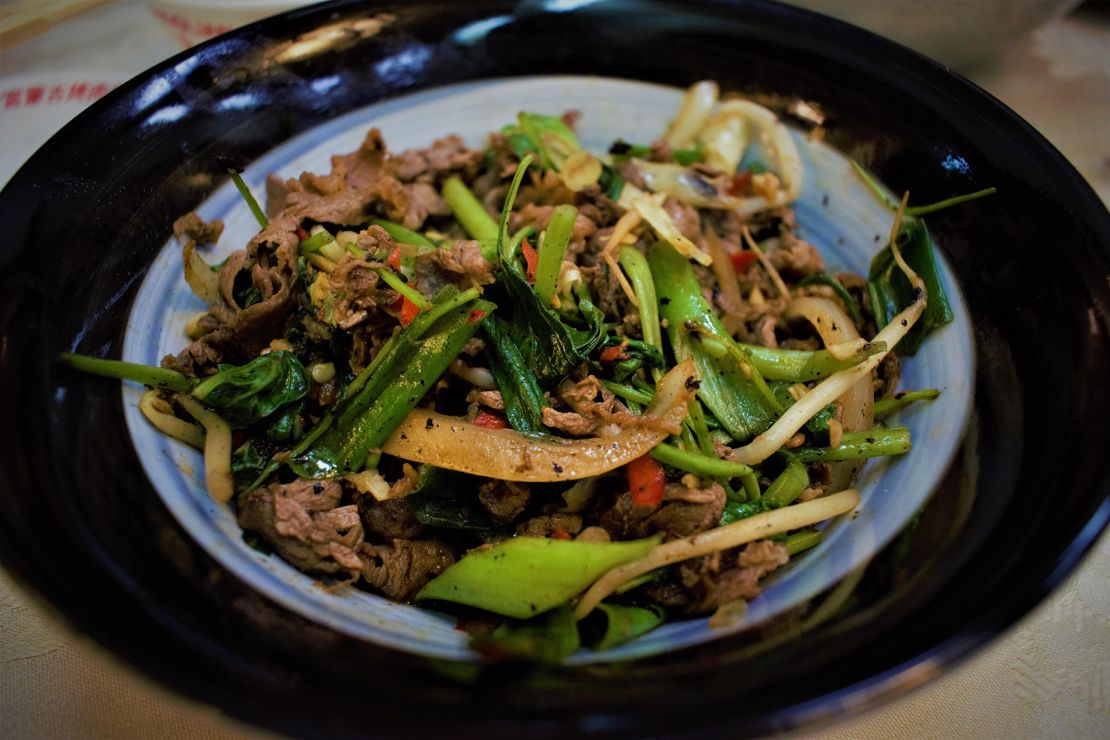

“Surprisingly, despite the name, Taiwan is the origin of Mongolian barbecue,” reveals travel enthusiast and native Taiwanese Erin Yang. “[It] consists of the combination of sliced meat, noodles and vegetables quickly cooked over a flat circular metal surface.”

Mongolian barbecue is a relatively new food trend, emerging in Taiwan in the 1950s and influenced by Japanese teppanyaki and Chinese stir-fry. It’s also popular in certain regions of China.

Beijing-based food and travel blogger Monica Weintraub says beef and lamb feature heavily in the north of the country.

“Whether you’re sharing a leg of lamb between four or five friends or ordering single lamb skewers (yang rou chuan), be expected to intake meat heavily doused in chili powder, cumin seeds and salt,” she says.

Fiji’s barbecue tradition has more of an underground approach compared to other nations.

Erin Yang explains: “Unlike many other barbecue styles, Fijian barbecue is cooked in a ‘lovo,’ an earth oven.”

Lovo involves piping-hot stones placed into a large opening in the ground to allow slowly smoked cooking.

“Ingredients such as pork, chicken, vegetables, taro root and seafood are wrapped in taro or banana leaves and placed onto the stones,” Yang says. “After 2-3 hours, the savory lovo will be ready to serve.”

Unearthing the pit-smoked food is met with jubilation from feasters, perhaps due to the hours-long wait for the cooking to be completed.

Umu, Samoa’s version of the barbecue, is similar to the underground cooking customs of Fijian lovo.

Avichai Ben Tzur, a travel writer/entrepreneur who’s spent significant time in the South Pacific, describes barbecue prep work as a family task.

“Young men of the extended Samoan family gather together to prepare the ‘umu,’ hours before the traditional Sunday feast commences… catching fresh fish or slaughtering a pig, collecting taro leaves and breadfruit from the family’s agricultural plot and cracking open coconuts for the palusami.”

The palusami, a Samoan staple made of coconut cream (often seasoned with onions, lemon juice and simple spices) wrapped in taro leaves, is “a delicious calorie bomb that cannot be resisted by Samoans,” says Tzur.

Gogigui (Korean for “meat roast”) is a favorite of both Koreans and international eaters.

Dining at a Korean BBQ usually consists of sliced beef, pork and chicken with an assortment of banchan (side dishes) and rice cooked in the center of a table, which is either cooked by the chefs or the diners themselves.

Should you choose to cook your own gogigui, “Masterchef Korea” finalist Diane Sooyeon Kang shares some tips.

“For thin slices of meat like chadolbaegi (thinly sliced beef brisket), you should lie it flat and cook it quickly for a few seconds on each side,” she says. “For meats like yangnyeom galbi (marinated short ribs), high heat and fire will be best as it will caramelize the outside while keeping the meat juicy inside.”

Jessica Mehta, who’s lived in Korea for a year, suggests: “You’re not really having Korean BBQ if you don’t pair it with soju, a clear liquor somewhat similar to sake.”

Though Peruvian cuisine is known the world over for ceviche and Pisco sour cocktails, one of Peru’s most traditional Incan cooking customs, pachamanca, is still under the radar to many.

Pachamanca (meaning “earth pot” in the Quechua language) involves digging to create a ground oven and lining the cavity with fire-heated stones to cook the food.

A variety of potatoes, corn, legumes and marinated meats are enclosed in banana leaves and placed into the earth oven for hours.

Authentic pachamanca are served sitting on the ground, and mostly take place on special occasions (especially religious ceremonies) and during harvest time every February and March.

Read the full article here